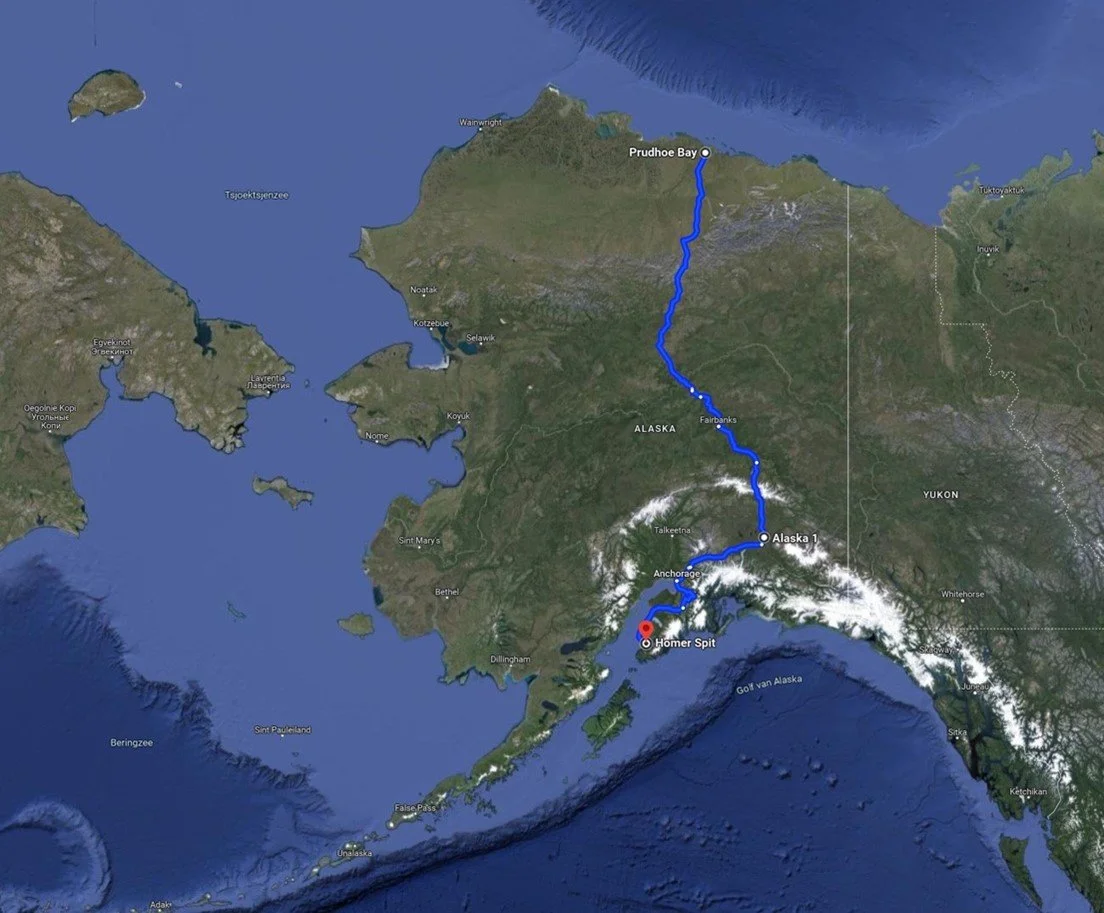

As I mentioned before, I knew Alaska still had something to show me in my final days there. I drove all the way to the other end of the road, to a small town called Homer. Homer is often described as the “end of the road” town. The final stop where the pavement ends into the sea. Here, salmon and halibut fishing plays a vital role in the town’s life and culture.

While in Homer, I was invited to visit someone’s cabin deep in nature, a place completely off the grid, without running water or electricity. This cabin was a humble shelter amidst towering trees and untouched wilderness. There, I got a firsthand glimpse of what life is like here: the daily challenges and the deep connection they have with the land. It’s a life that requires self-sufficiency and respect for nature, but also one that offers immense freedom and fulfillment. When it was time to say goodbye, I was even given several cans of salmon to take home. Every summer, they catch salmon and prepare it carefully to last through the long winter months. That very evening, I ate one of those cans for dinner and let me tell you, it tasted incredible.

Throughout this journey, I spoke with many people about why they chose to leave their old lives behind and come to Alaska. What were they searching for? And did they find it? They say out here: “You’re either running away from something or towards something.” But beyond that, I discovered how Alaska offers a kind of healing, a chance to rebuild and to find peace. The raw wilderness, the vast open spaces create an environment where certain people can confront their past, heal old wounds, and rediscover themselves. It’s a place that demands both courage and humility, but also rewards with a sense of renewal.

On my last day, I headed to Anchorage, Alaska’s largest city, home to around 290,000 people. Even so, Anchorage still feels quiet and spacious compared to Amsterdam, which has over 800,000 residents packed into a much smaller area. Returning to the city was a sharp contrast to the solitude and calm of the wilderness. And believe me, it was nothing compared to arriving at Schiphol Airport in the Netherlands, where the crowds and noise hit me all at once.

Now I’m back home, and I’m enjoying the little luxuries after a month of living in a camper; like waking up warm, standing upright in the shower, and not having mud on all of my belongings, I already miss Alaska deeply. The freedom, the raw beauty, and the genuine human connections I made there have left a lasting mark on me. It’s made me realize how much we take for granted but also how important it is to stay connected to nature and to ourselves.

In the coming weeks, there might be fewer newsletters, not because I’m stepping away from the project, but because I have so much footage and material to edit. I’m really looking forward to diving into this new phase and sharing the results with you all.